local media

local news

audience

myth of the local

Czech Republic

Shattering the Myth?

Audiences’ Relationship to Local Media and Local News Revisited

Lenka Waschková Císařová, Masaryk University

Jakub Macek, Masaryk University

Alena Macková, Masaryk University

Keywords

Abstract

The relationship between news audiences to local media, more specifically local news, is presumed as intensive, and news audiences used to be described as highly interested in local news. This presumption is concurrently criticized as an inaccurate myth of the local, which draws mainly upon U.S. or U.K. experiences, inapplicable to other media systems. This exploratory study focuses on Czech local audiences and provides evidence-based reconsideration of the myth. Employing data from quantitative survey of the Czech adult population and qualitative interviews,this study demonstrates local news consumption by Czech audiences. [read more=”Read More” less=”Read Less”]Findings suggest that the audiences of local news—typical for their relatively low interest in local news—constitute a serious challenge for the prevailing optimistic notion of local news audiences. The study employs cluster analysis of Czech audiences of local news and qualitative interviews to assess a more nuanced understanding of the local audiences, and more specifically considers contextual influences forming the Czech local news media.

[/read]

Introduction

A udiences are the key factor of media performance, the reason for its very existence. Therefore, it is quite striking that audience research does not play a stronger role in journalism studies (cf. Costera Meijer, 2012). The interest in audience needs lead media to deepen and extend marketing research, which creates an impression media know their audience well. But as Costera Meijer (2012, p. 755) accurately points out, “the paradoxical effect is that by refusing to pay real attention to ratings conventions, which have news exposure as the key measurement…, many journalists (and journalism scholars) are inclined to take these figures as a measure for their audience’s news interest” (cf. Pauly & Eckert, 2002).

However, we assume that this topic is even more relevant in a tight and fragile subsystem of local media. Hess and Waller (2017, p. 13) call the topic of local audience needs and habits “paramount”. Surprisingly, the topic of local audience is not widespread considering the increasing importance of the topic of local media in scholarly discourse (e.g. Ali, 2017; Hess & Waller, 2017; special issue of Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies, 2017; Nielsen, 2015).

The aim of this exploratory text is (1) to offer an empirically grounded reconsideration of the relationship between local media, specifically local news, and Czech audiences, and (2) to point out that it is not realistic or pragmatic to apply a “one size fits all” approach in defining and assessing news audiences and mainly local news audiences regardless of national or local specifics. Centering the specifics of the Czech media system, this paper analyses audiences’ reception of local news in the broader context of regional, national, and foreign news. Using hierarchical cluster analysis and multinomial logistic regression for statistical inquiry of the quantitative data set and broadening the results with findings from qualitative interviews, we point out the major characteristics of local news audiences in the Czech Republic, which enables us to focus on their specifics when compared to prevailing notions of local audiences.

Local audiences

The relationship between audiences, local media, and local news is presumed to be strong and close. This assumption is called the myth of the local (cf. Pauly & Eckert, 2002, p. 311), which draws on two persistent arguments: Firstly, for audiences, local issues are the most important media content (Aldridge, 2007; Hollander, 2010; Lauterer, 2006; Mair, Fowler, & Reeves, 2012; Pácl, 1997). Secondly, local media consumption is a key part of life in a local community (Fenton, Metykova, Schlosberg, & Freedman, 2010; Franklin, 2006; Rothenbuhler, Mullen, DeLaurell, & Ryu, 1996).

There is—mainly in relation to the U.S. or U.K. media systems—broad empirical evidence supporting both arguments (Fenton et al., 2010; Fletcher, Radcliffe, Levy, Nielsen, & Newman, 2015; Hollander, 2010; Newman, Fletcher, Kalogeropoulos, Levy, & Nielsen, 2017; Newman, Fletcher, Levy, & Nielsen, 2016; Newman, Levy, & Nielsen, 2015; Ofcom, 2009; Pew Research Center, 2015). In the existing studies, we can read about “hunger for local news” (Hollander, 2010, p. 6), or that “local news matters deeply to the lives of residents” (Pew Research Center, 2015, p. 4).

More particularly, according to research conducted in three metro areas in the U.S., the majority of local media audiences still follow local news closely with local TV as the news source. In addition, civically engaged audience members express stronger connection to local news when compared to other audience members and use a more diverse set of news sources (with dailies and personal interactions as more common sources of news) (Pew Research Center, 2015, pp. 4, 5, 8, 9).

At the same time, nine out of ten U.K. adults regularly consume some form of local news or other local content (Ofcom, 2009). These findings confirm data from Reuters Institute digital news reports, which in 2016 suggested that among different types of news, audiences from various national states are the most interested in local news (Newman et al., 2016, p. 97).

However, the ingrained myth of the local is also criticized for its vague definitions or for being abused in media discourse (Nielsen, 2016; Pauly & Eckert, 2002). Pauly and Eckert define the myth of the local as, “the belief that newspapers are most true, pure, real, and authentic when they honor their responsibility to ‘the local’”. Moreover, this myth of the local arises from “widely told stories that dramatize deeply held habits of mind, group beliefs, and styles of action” (Pauly & Eckert, 2002, pp. 310–312).1Cf. Nielsen, who works with a similar concept called the folk theories of journalism, describing it as, “actually existing popular beliefs about what journalism is, what it does, and what it ought to do.” This understanding might increase readers’ engagement with journalism, but Nielsen takes the concept as a tool enabling researchers to ask new questions to understand journalism better (Nielsen, 2016, pp. 1, 3).

Pauly and Eckert not only criticize vague definitions of local as employed by both journalism professionals and scholars (2002, p. 311), but argue that audiences and their assumed strong interest in local media/news is more of a theoretical construct than reality. They point out that local media often turn to marketing research to solve a decline in audience interest and that various survey results claiming to confirm importance of local media suggest in fact only that

…neither the newspaper nor the reader exactly knows what makes a paper ‘local.’ And readers may not actually read the news they call for. Their responses may speak to their own myths of community. Nor have all marketing researchers agreed that adding local news would attract more readers. (2002, pp. 313–314)

Therefore, in this study we identify ourselves with these critiques of the myth of the local as we find the myth as hardly a generalizable depiction of local media and news and their audiences. In line with this position, we suggest that the notion of local media and local news employing the myth of the local and applied by some scholars and journalists on various media realities are often overly optimistic, inherently normative, and in some aspects only loosely valid theoretical constructs. In order to avoid the myth of the local, local media and local news have to be understood as contextually specific, at least from a cross-cultural and cross-national perspective—therefore, the “one size fits all” approach has to be left aside and, as Nielsen (2016) points out, we need to try to ask new questions which will help us see the problem of local media and local news in a new and more contextually sensitive light.

This brings us to our main question: How does the above-mentioned assumption about “hunger for local news” (Hollander, 2010) apply to another, i.e. non-U.S. or non-U.K. media, system, or would such application shatter the myth of the local? In the case of the Czech Republic, which represents one specific European media environment, the subsequent question is: What is the relationship between Czech audiences and local media, and more specifically local news?

Testing ground: Czech local media

As suggested above, the contextual specifics of the Czech media system—distinct in several key aspects from the U.S. or U.K. situation—could serve as a rich testing ground for our assumption: Czech local media are part of a transitive media system which comes with changes both on the level of audience-media relationship and politics/legislation level (Gulyás, 2003; Waschková Císařová, 2013).

In addition, the local media functions are under pressure of commercialization (cf. Pauly & Eckert, 2002), the demise of existing business models, ownership concentration, and closures of local media (Waschková Císařová & Metyková, 2015).

According to the data set employed in this study, Czech audience consumption patterns are in the broadest view quite similar to the ones in other non-transitive countries. In 2014, TV broadcasting had a prominent position as the main source of news and even as a source of popular content; nine out of ten respondents received news and two thirds of them received news every day; nine out of ten news consumers were watching news on TV; 46% of news consumers received news online and the respondents were strongly interested in soft news (weather – 69 %; crime – 39 %; sports – 37 %) (cf. Fletcher et al., 2015; Macek, Macková, Škařupová, & Waschková Císařová, 2015b; Newman et al., 2015; Newman et al., 2016; Newman et al., 2017).

However, the structure of the Czech local2Within the Czech media system, the term local media denotes media produced and distributed only at the municipal and district level, while the term regional media refers to media produced and distributed at the regional level (see Waschková Císařová, 2016). However, due multiple reorganization of basic units of state administration in the 20th century, the precise definition of the local and the regional as well as shared understanding of these terms among media producers and audiences struggle with a difficulty—in the 1990s the smallest administrative and political unit, a district, was replaced by a much larger region. This complicated the very existence of “non-national” media, which had to choose their area of production and distribution repeatedly (for more see Waschková Císařová, 2013, pp. 19–20). media is quite specific when compared to the U.S. or U.K. contexts. In the Czech Republic, the print media is prevailing, local TV has only a weak position in the market, and local radio and online local pure players are almost non-existent.3The amount of internet access, broadband access, and internet use by individuals corresponds to the EU average. In terms of internet access, percentage of households who have internet access at home (all forms of internet use included, population 16–74) was 78% in the Czech Republic, and 81% in the whole of the EU in 2014 (the year of our survey data collection) and 83% in the Czech Republic and 87% in the EU in 2017. Percentage of households (with at least one member aged 16–74) with broadband access was 76% in the Czech Republic and 78% in the EU in 2014, and 83% in the Czech Republic and 85% in the EU in 2017. Internet use by individuals (aged 16–74) was 80% in the Czech Republic and 78% in the EU in 2014, 85% in the Czech Republic and 84% in the EU in 2017 (for more see Eurostat, 2017). There were 132 local and regional newspapers in 2009; 73 of them, the only dailies, were part of one publishing chain, and the rest were mainly local weeklies (their number was and still is decreasing). Unfortunately, more current numbers are not available (Waschková Císařová, 2013). Nowadays there are 13 regional public service radio stations, the only non-national radios with news. They all are part of the public service broadcasting corporation Český rozhlas [Czech Radio] (see Český rozhlas, 2018). Besides that, there are seven regional commercial TV stations, several dozen local commercial TV stations (partly organized as municipal TV stations with limited news coverage; 18 of them are part of two different associations for local and regional TV stations) and regional news in public service television (see Česká televize, 2018; Televize Nova, 2018; Televize Prima, 2018). We assume that the lower importance of local news for the Czech audiences could be related to the weaker position of local TV in a society with TV as the strongest news source (Aldridge, 2007; cf. Pew Research Center, 2015).

Unfortunately, there are limitations to the historical information available about audience interest in local news in the Czech Republic. The sole source, a survey from 1996 covering only one Czech region (North Moravia), suggests that audiences were more interested in regional news among all press sections (Pácl, 1997, p. 38). Nevertheless, Pácl formulated a possible explanation to the decline in interest of regional news and, at the same time, a reason for specific development of local and regional media in the Czech Republic, arguing, “Yet more recently, the newspapers cost one Czech crown, so many families have subscribed or have regularly bought more dailies, usually one national and one regional. (…) Today they are only buying one title” (Pácl, 1997, p. 38) and more often it is the national daily (cf. Gustafsson, Örnebring, & Levy, 2009).

Another assumption about the specific relationship of Czech audiences to local media and local news draws on criticism that there are quality issues with the local media and concerns about the professionalism of local journalism. Research on the professional role of Czech regional journalists conducted between 2003 and 2005 have observed low levels of professionalization among local journalists in the study (Volek, 2007). Furthermore, audiences should perceive that local news are “about them,” but as a consequence of ownership and organization centralization, the content of the Czech print media (namely the largest chain of district dailies) has been significantly de-localized in recent years (see Waschková Císařová, 2016).

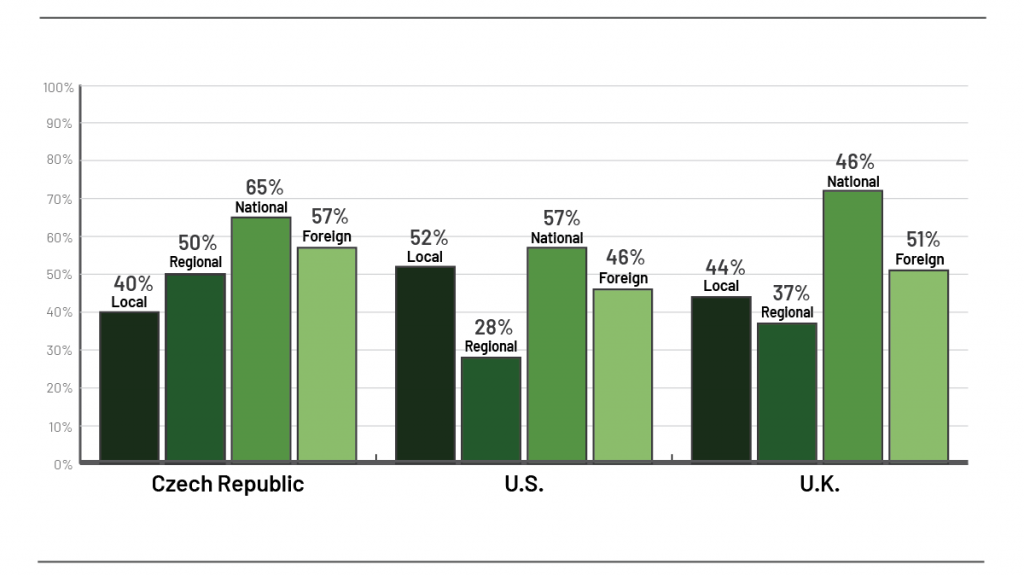

These reasons lead us to the assumption that in the Czech transitive media system, the audience’s relationship to local media and local news relationship cannot be treated as identical or similar to major non-transitive media systems (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Audiences’ interest in news topics

Sources: Reuters Institute digital news report 2015; Reuters Institute digital news report 2015, supplementary report.

In other words, the U.S. or U.K. experience cannot simply be extended to the Czech Republic. The Czech context, which includes social, political, and historical specifics of the Czech local media environment have to be taken into account. Therefore, the case of Czech local media audiences could serve as important information to reconsider the general theoretical notion of local media and local news and their role in the lives and practices of audience members.

Methods

The analysis presented in this paper draws on a data set from a survey of the Czech adult (age 18+) population. To obtain a sample reflecting demographic structure of Czech society, the survey employs quota sampling (based on age, education, sex, and the size and region of residence) and computer-assisted personal interviewing. Interviews were conducted between October 18th and November 30th of 2014 from a sample of 1,998 respondents. The survey is part of a broader project entitled New and old media in everyday life: media audiences at the time of transforming media uses (Czech Science Foundation, GP13-15684P) and was primarily designed to explore the full range of Czech audiences’ media-related practices. For the purpose of this exploratory paper, we focus on selected measures related to the research problem formulated above.

In the first analytical step, we use hierarchical cluster analysis based on Ward’s criterion. On basis of criteria (variables) selected by a researcher, the method enables the organization of the sample into clusters (types) with minimal inner variance of the selected criteria. The method proceeds from “leafs” to “a chunk”, i.e. in each hierarchical step it connects cases on the basis of their similarity in selected criteria starting with individual cases and ending up with several larger clusters (or with one cluster equal to the whole sample in the very last step). In every step, the number of provided clusters decreases while their inner variability increases (as the clusters include higher number of cases). Selection of a particular step (cluster solution) for report then usually depends upon reasonable interpretability of resulting clusters and other criteria, such as number of cases included in resulting clusters. The cluster analysis introduced in this paper was entered by four dichotomous variables indicating participant’s interest in local news, interest in regional news, interest in national news, and interest in foreign news assessed through the following question: “You have said that you receive news. What types of news information are you interested in?” and by marking the particular type of news on a list. We expected that the participants’ interest in local, regional, national, and international news may combine in specific patterns that might help us to identify the position of local news in the Czech audiences’ news consumption. Therefore, our intention was to assess these potential patterns and their distribution across the Czech population. The cluster analysis serves this intention well as it delivers a typology of the participants based on their preferences regarding certain localness of the news they consume. Out of the cluster solutions consisting of 2–7 clusters, we have decided to work further with a 5-cluster solution as it offers a detailed typology with clusters still usable for the subsequent regression.

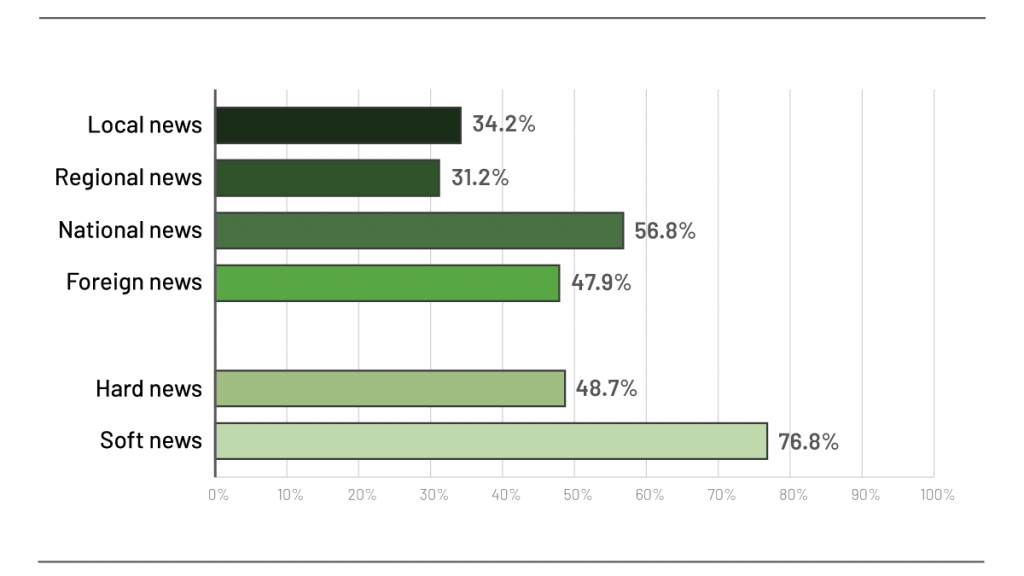

Figure 2: Distribution of interest in particular news types (n=1,998)

Source: Authors’ own.

In the second step, the five types of Czech news audiences identified in the cluster analysis (for detailed description of the clusters see below) were used as dependent variables in the multinomial logistic regression. This part of the analysis enables us to identify predictors of the five types of news audiences, i.e. it provides us with the possibility to tackle other crucial aspects in which the five clusters of news audiences differ. Our decision was to take into account basic social and demographic characteristics of the participants, other important characteristics of their news consumption possibly interfering with their attitudes to news, and location of their residence considered as a presumably crucial influence on the participants’ interest in local news. Therefore, measures entering the regression as independent variables were: age, sex, and education (as proxy variables for socio-economic status), frequency of news consumption, interest in hard news, interest in soft news, and centre/periphery (location of the participant’s residence).

The independent variables were assessed as follows: The dichotomous variables of interest in hard news and interest in soft news (see Figure 2) are recoded from the same questionnaire item as the above-explicated variables on news localness, but from other choices offered on the list. Interest in hard news includes selection of political news, economic news, and/or science and technology news; interest in soft news includes selection of news on culture, sports, and/or crime and traffic.

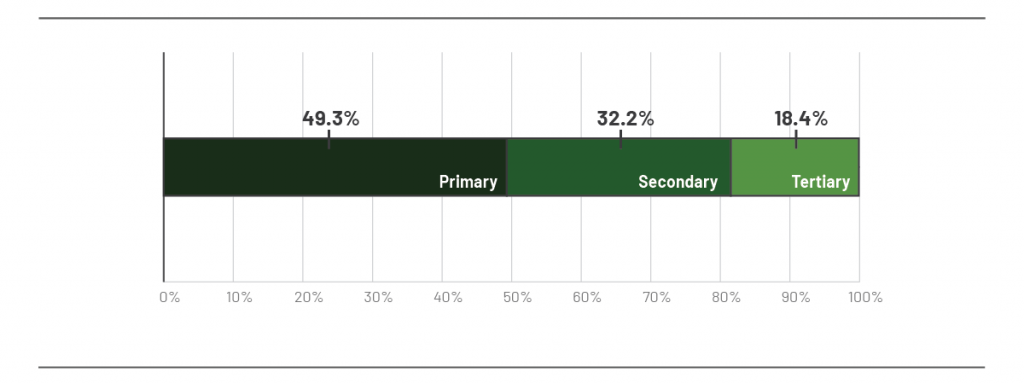

The ordinal variable of education (see Figure 3) ranges from 1 to 3 and consists of the categories of primary education (1), secondary education (2), and tertiary education (3).

Figure 3: Distribution of education (n=1,998)

Source: Authors’ own.

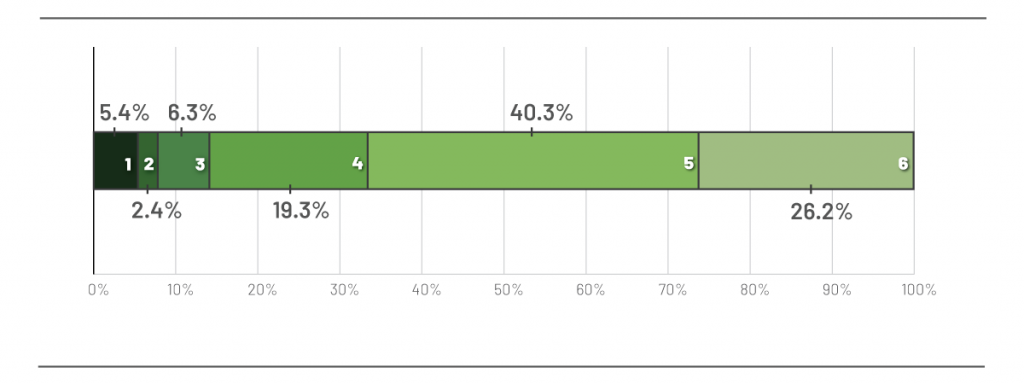

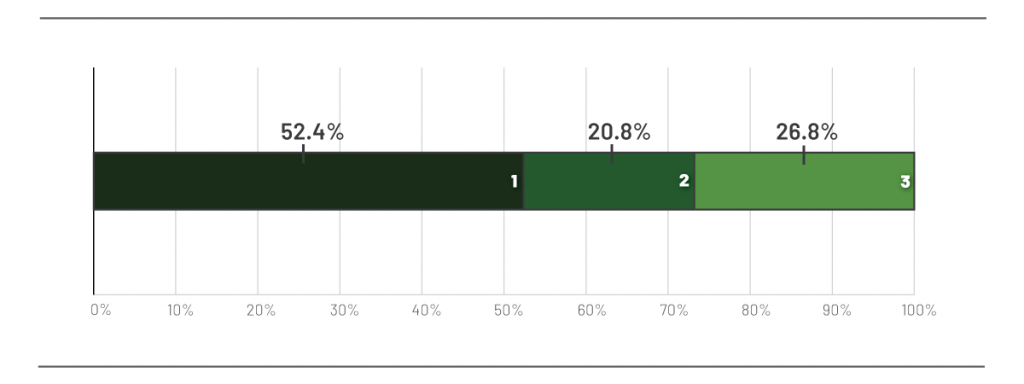

The ordinal variable of frequency of news consumption (see Figure 4) indicated how often the participants read, watch, or listen to news. The scale ranging from 1 to 6 included categories 1) “never” (5.4%), 2) “less than once per month” (2.4%), 3) “usually several times a month” (6.3%), 4) “usually several times a week” (19.3%), 5) “usually once a day” (40.3%), 6) and “several times a day” (26.2%).

Figure 4: Distribution of frequency of news consumption (n=1,998)

Source: Authors’ own.

The ordinal variable of centre/periphery (see Figure 5) ranges from 1 to 3 and identifies participants living in 1) a city or a town (52.4%), 2) suburbs (20.8%), 3) the countryside (26.8%). Rather than size of particular site of residence, the variable indicates its position on a centre/periphery scale.

Figure 5: Distribution of centre/periphery variable (n=1,998)

Source: Authors’ own.

Moreover, the second part of the research consists of a series of qualitative interviews conducted in April and May 2014 with a specific sample of 22 politically and publicly active citizens aged 15–60 years. Interviews primarily focused on the civic practices of respondents in both cities as well as small towns and villages to understand the role of various media in these practices. It was a pilot study mainly addressing the role of media technologies in political and public engagement, and it preceded the quantitative survey (for more details on interviewing methods and analysis see Macek, Macková, & Kotišová, 2015a). Moreover, the quantitative survey of this study focuses on the relationship to local news, while the more general topic of local media is emerging only in the qualitative interviews. The qualitative approach plays an irreplaceable role in researching local media and local news topics (see e.g. Anderson et al. in Nielsen, 2015; Fenton et al., 2010) as it enables researchers to examine audiences in greater depth (see McCollough, Crowell, & Napoli, 2016). As Hollander (2010, p. 13) puts it, “the strength of the analyses … nationally representative sample … is also its weakness in answering questions that may best be answered at a local or regional level.”

Findings

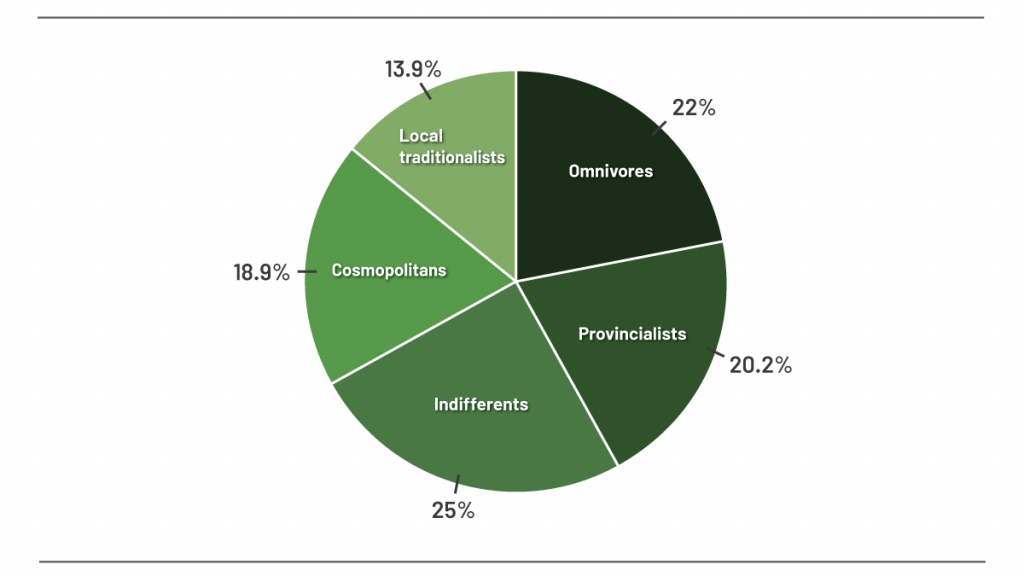

As mentioned above, the cluster analysis entered by dichotomous variables indicating interest in local, regional, national, and foreign news suggested five clusters, i.e. types of audience. These clusters are labelled (cf. Elvestad, 2009) as omnivores (22% of the sample), provincialists (20.2%), indifferents (25%), cosmopolitans (18.9%) and local traditionalists (13.9%) (see Figure 6). Regarding the participants’ relation to locality of news, they represent clearly distinct types of news consumption (see Table 1).

Figure 6: Distribution of the clusters within the sample (n=1,998)

Source: Authors’ own.

Table 1: Distribution of the entering variables within the clusters (n=1,998)

| Interest in local news | Interest in regional news | Interest in national news | Interest in foreign news | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omnivores | 72.30% | 100% | 86.80% | 100% |

| Provincialists | 21.30% | 45.20% | 78.70% | 0% |

| Indifferents | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Cosmopolitans | 0% | 0% | 69.30% | 100% |

| Local traditionalists | 100% | 0% | 62.60% | 50.20% |

Per cent within the cluster expressing interest in particular type of news.

Source: Authors’ own.

The indifferents are typical for not expressing interest in any of the assessed types of news while the omnivores are, in contrast to them, interested in more or less all the four types of news.4It is worthwhile to note that the fact that the participants in the cluster of the indifferents do not express interest in any of the four types of news (local, regional, national, or foreign news) does not imply that they are disinterested in all news or even in other media content. Illustratively, only 21.6% of them are pure news non-consumers while 58.1% of them are interested in soft news (on culture, sports, celebrities, etc.), 31.4% in hard news (on economics, science & technologies etc.), 39.2% of them can be considered as regular book readers, 85.9% watch films and 65.8% watch TV at least once a month. In other words, these participants are indifferent only regarding regionalism of news and must be treated as such. The other three clusters are characterized by omitting some of the news types and by interest in some other news types. In the cluster of the provincialists, we observe lack of interest in foreign news; the cosmopolitans are interested in national and foreign news but not in local and regional news; and the local traditionalists—constituting, along with the omnivores, the main body of the local news audience—are not interested in regional news, but more than a half of the group expresses interest in national and foreign news.

The multinomial logistic regression then enables us to identify the predictors constituting differences between the cluster of the indifferents and the other clusters. In other words, in the analyses entered by the above-described variables, we assume the indifferents as a reference category and we look for factors increasing or decreasing odds for moving from the cluster of the indifferents to the other clusters (see Table 2).

Table 2: Multinomial regression, parameter estimates (n=1,998)

| The reference category: Indifferents | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omnivores | Provincialists | Cosmopolitans | Local traditionalists | |||||

| B (S.E.) | OR | B (S.E.) | OR | B (S.E.) | OR | B (S.E.) | OR | |

| Intercept | -5.290 (.472)*** | -4.041 (.407)*** | -2.901 (.386)*** | -3.579 (.442)*** | ||||

| Centre/periphery | -.112 (.088) | .894 | -.008 (.086) | .992 | -.199 (.088)* | .820 | -.211 (.095)* | .810 |

| Frequency of news consumption | .790 (.084)*** | 2.203 | .862 (.076)*** | 2.368 | .710 (.074)*** | 2.035 | .686 (.083)*** | 1.986 |

| Hard news | 1.222 (.165)*** | 3.395 | -.550 (.160)*** | .577 | .312 (.157)* | 1.366 | .109 (.170) | 1.116 |

| Soft news | 1.010 (.224)*** | 2.746 | -.026 (.184) | .975 | -.063 (.184) | .939 | .397 (.213) | 1.487 |

| Age | .017 (.005)*** | 1.017 | .010 (.005)* | 1.010 | .003 (.005) | 1.003 | .008 (.005) | 1.008 |

| Sex (male) | .087 (.154) | 1.091 | -.210 (.151) | .811 | .161 (.152) | 1.175 | -.440 (.166)** | .644 |

| Primary ed. (ref. cat.: Tertiary ed.) | -.792 (.211)*** | .453 | -.178 (.222) | .837 | -.609 (.211)** | .544 | -.182 (.236) | .833 |

| Secondary ed. (ref. cat.: Tertiary ed.) | -.603 (.221)** | .547 | .037 (.232) | 1.037 | -.345 (.220) | .708 | -.145 (.249) | .865 |

| Model c2 (df) | 5318.509 (32)*** | |||||||

| R2 (Nagelkerke) | .310 | |||||||

| R2 (Cox & Snell) | .297 | |||||||

Note. B = Unstandardized regression coefficient. SE = Standard error. OR = Odds ratio. *** p =< .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05.

Source: Authors’ own.

As for the demographic variables, age increases odds for the omnivores (for each year OR=1.017) and for the provincialists (for each year OR=1.010), being male decreases odds for moving to the cluster of the local traditionalists (OR=0.644) and lower education strongly decreases odds for being an omnivore (for sec. ed. OR=0.221, for primary ed. OR=0.211) and a cosmopolitan (OR=0.544).

When compared to other predictors, frequency of news consumption comes with strongest and identically oriented effects for all the clusters in relation to the cluster of the indifferents. Simply and unsurprisingly, the indifferents differ from the other samples by lower frequency of news consumption. With every point at the six-point scale of frequency, odds to be an omnivore (OR=2.203), a provincialist (OR=2.368), a cosmopolitan (OR=2.035) as well as a local traditionalist (OR=1.968) increase more or less twice.

Interest in hard news increases the odds strongly for being an omnivore (OR=3.395) or slightly for being a cosmopolitan (OR=1.366) while it moderately decreases odds for being a provincialist (OR=0.577). Therefore, along with interest in foreign news, interest in hard news marks another key difference between the omnivores and the provincialists. In contrast, interest in soft news increases odds only for being an omnivore (OR=2.746), underlining the general interest in news typical for the participants included in the cluster.

To summarize briefly, the omnivores consume all indicated types of news (local, regional, national and foreign news, hard news, soft news). Omnivores are older and with higher education than the indifferents; the provincialists are not interested in foreign news, they prefer rather soft news and are, again, older than the indifferents; cosmopolitans do not consume local and regional news at all and have a higher education than the indifferents as a group; the local traditionalists are specific for their strong interest in local news but they do not express any interest in regional news, they live closer to the periphery and they are more often women.

Data from qualitative interviews, though quite specific as being politically and publicly active at the local level, provides a nuanced understanding to reveal some specifics of audience attitudes towards local media and local news that were not covered by measures used in the survey.

In general, we may observe a clear distinction between village and city respondents in terms of local topics and local media consumption (cf. Pew Research Center 2012). For one of the interviewees living in villages, local topics and local media are more important in the sense of “the closer, the better.” High levels of interest in local politics are typical, even among other respondents who experience stronger ties to the locality. These respondents feel absorbed by local topics and perceive consumption of local media as important:

“I am interested in this region because I live here, so I want to know, what is going on here (…). I subscribe all the newspapers from the region.” (Interviewee 15)

“I try to regularly visit municipality web pages, read local newspapers, sometimes watch local TV.” (Interviewee 19)

Moreover, the two quotations illustrate that the audience members differ in labelling sub-national media level. Both respondents speak about local (district) media, but the first respondent refers to local media and the second respondent to regional media. This difference refers to the aforementioned historically conditioned confusion in finding the clear distinction between “the local” and “the regional” in the Czech Republic. On the one hand, it shows variability of in vivo terminology used by the audience members in their categorization of media. On the other hand, this might potentially refer to validity limits of the measures used in quantitative surveys (therefore, in our questionnaire we have minimized the problem by explicit classification of district media as local, not regional media).

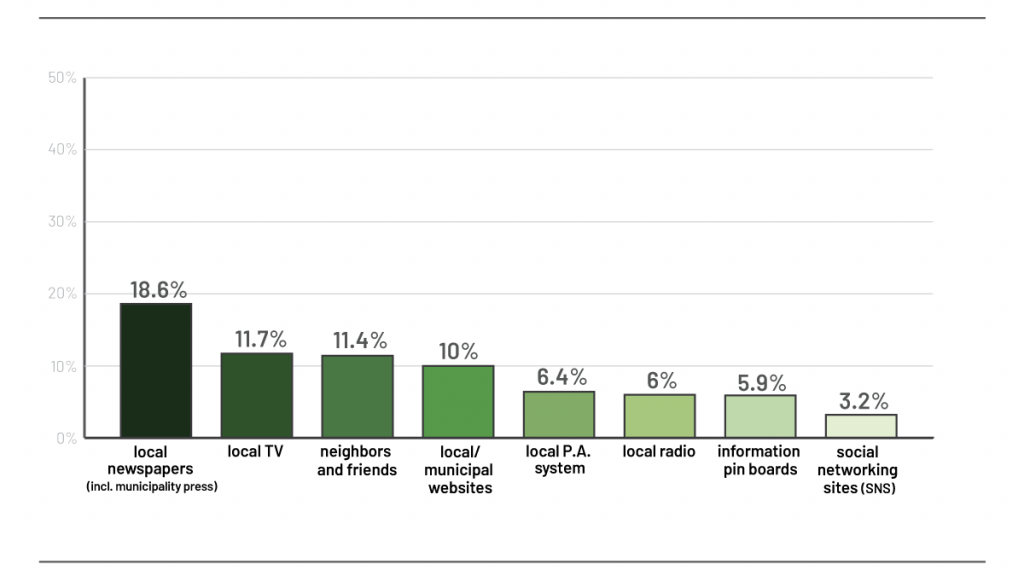

In contrast to the respondents living in urban areas, the respondents living in villages were talking in the interviews about their preference of newspapers (cf. Fenton et al., 2010): including local and municipality press through regional press to national dailies. This brings us back to the local media structure in the Czech Republic typical for lack of TV and radio as source of local news – the local media environments in the Czech Republic are simply dominated by press media (see Figure 7). Findings from the survey confirm that print media serve as the main source of local information.

Figure 7: How the audience members obtain local news (n=1,998)

Source: Authors’ own.

The respondents of the qualitative part of the research living in urban areas are typically interested in national media and national news. Furthermore, this group of respondents are generally more critical about media quality, specifically objectivity. Respondents living in urban areas also consume more online media and use social media.5The difference between internet infrastructure at the national level and in rural areas is not as substantial as could be expected. The last data are from 2012 and the percentage of standard broadband coverage at the national level was 98% and in rural areas, 88%. Percentage of households having subscribed to a broadband connection was 59% in 2012 in rural areas and 61% at the national level (Eurostat, 2013). The proportion of our survey participants using the internet on daily basis by degree of urbanization: 65.4% cities; 58.8% towns & suburbs; 57.3% rural areas (proportion of users in cities differs from proportion of users in towns & suburbs and in rural areas at the .5 level; proportion of users in towns & suburbs and in rural areas do not differ significantly) (Macek, Macková, Škařupová, & Waschková Císařová, 2015b; cf. Eurostat, 2016).

In contrast to the urban respondents, those living in villages provide a more diverse picture of sources of information they use. Firstly, respondents in this group emphasize the role of direct, interpersonal communication in their news gathering practices, though even the younger respondents discussed their preference for personal interactions over new media. In addition, actual promotion of events in villages included in the qualitative inquiry usually takes place offline, mainly through print media. As respondents mention:

“I communicate with my neighbours when I walk down the village, when buying in the local shop. When we meet, I invite them to the event.” (Interviewee 16)

“It’s definitely better here than in the city, people communicate here and prefer interpersonal communication, not media or something similarly modern.” (Interviewee 16)

“We live here everyone in one pile, so there’s no problem to meet the people.” (Interviewee 19)

Secondly, even the usage of various types of media is quite diverse in the rural contexts— respondents from villages use municipal press, municipal web pages, pin-boards, or a local P.A. system (cf. Figure 7, above). As an illustration of this, one of the older respondents living in a village compares their municipal pin-board to a Facebook wall, and another person cuts out event invitations from the municipal press to display them somewhere at home.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper comments on the goal to reconsider the audiences’ relationship to local media and local news, and critiques those universalistic notions of local audiences that tend to avoid specifics of particular national contexts. When assessing local news audiences in the Czech Republic, we intended to find out whether the Czech audiences in their relationship to local media and local news are specific enough to shatter both the myth of local (Pauly & Eckert, 2002) as well as the attempts for generalization of the notion of local media and news stemming from the U.S. or U.K. experience.

Quantitative data suggests that Czech audiences of local news are similar to other local audiences researched in Western countries, specifically in regards to the older age of local news audiences (Hollander, 2010; Nielsen, 2015; Wadbring & Bergström, 2017). In other aspects, however, the local news audiences in the Czech Republic differ from local audiences in Western countries. We show a lower interest in local news (see Figure 1) and show the use of print media as the main channel of local news (cf. Aldridge, 2007; Nielsen, 2015; Pew Research Center, 2015) – though similar patterns can be observed in Norway (Skogerbø & Winsvold, 2011).

The cluster analysis and regression model enable a more nuanced look beyond these descriptive comparisons revealing more principal arguments for shattering the myth of the local. The typology of Czech news audiences provided by the cluster analysis suggests that there are no “purely” local audiences (or, in other words, a local audience in singular); only in three clusters out of the five identified is the interest in local news observed. The omnivore audience is interested in all types of news while the provincialists audience and the cluster of local traditionalists avoid regional news. In each of the clusters, the interest in local news is specifically and differently intertwined with interest in other types of news such as regional and foreign news with hard and soft news. This is interpreted as an indication of specific variations in the audiences’ relationship to public space and its geography as well as to variability in the audiences’ relationship to locality. In other words, we argue that even within the particular national context the role of local media and local news is perceived and consumed by audiences and is far from being monolithic, deserving further assessment.

Furthermore, the variability of the local audiences is underlined by the findings from qualitative interviews. Though respondents were quite atypical, as they were selected as representatives of publicly and politically explicitly active citizens, the contrast between urban and village contexts might be found illustrative. In smaller, spatially and socially condensed communities, we can observe specific importance attributed both to local media and non-mediated interactions and, at the same time, broader repertoire of the information channels. This, in the case of smaller local communities, supports the myth of the local newspapers as “parish pumps” of small localities (cf. Pauly & Eckert, 2002). At the same time, these differences in experiencing and using local media further emphasize our argument that the “one size fits all” notion of local audiences, media, and news is rather misleading.

Besides the evidence provided directly by the survey and qualitative interviews, the aforementioned broader contextual specifics forming the Czech local media and their audiences deserve to be considered.

The contextual point of view suggests that it remains slightly unclear what domestic media actually belong to the category of local media. Czech audiences as well as local and regional media traditionally have some difficulties in finding a clear distinction between local and regional news and media as the spatial, political, and symbolic distance of “the regional” from “the local” has changed repeatedly along with the changes of organizational structure of the Czech state. Importantly, the former existence of districts as sub-units of regions was and continues to be linked with the publication of district media (both dailies and weeklies). This category of media is usually classified as local media (as is the case in this study’s survey), yet the position of this media at the scale of local–regional is, in fact, problematic both for Czech audiences and for the publishers as the actual local focus is (especially in the chain dailies) often weakened (cf. Waschková Císařová, 2013).

The overall “hunger for the local news” observed in the case of the Czech audiences is lower in comparison to the U.S. or U.K. contexts (see Figure 1) which may find the following contextual explanations: Firstly, we interpret this lower interest in local news as an indirect effect of the position of newspapers as of the main channel of local news: the newspaper readership suffers from general decline (Macek et al., 2015b) and, therefore, so does the readership of local media. And, while in the 1990s the decline of local print media was interpreted as resulting mainly from an increase of prices of national and regional/local titles (Pácl, 1997), nowadays the socio-technological change can be blamed—with younger audiences preferring online media, as newspapers are read by a shrinking older audience (Macek et al., 2015b; Wadbring & Bergström, 2017). Secondly, the lower interest in local media may find its explanation in unfulfilled expectations of the Czech local audiences, as studies suggest “their” local journalists were recently found as less professional (Volek, 2007) and as producing poor quality journalism. And thirdly, it has been suggested that the Czech local audiences perceive local media and local news as losing their local character due to their ownership, organization, and content centralization (Waschková Císařová, 2016).

These contextual topics, obviously deserving of further empirical attention, clearly circumscribe the Czech local news media and their audiences as specific enough to shatter the myth again. Regarding more general significance of the findings, the study is in line with other research addressing consumption of local media as differing across national contexts (cf. Hollander, 2010; Pew Research Center, 2015; Skogerbø & Winsvold, 2011; Wadbring & Bergström, 2017). Data from our quantitative and qualitative inquiry suggests that specific national environments come with specific local media and local audiences that cannot be assessed as mere variations of the already well-researched local audiences. Moreover, as such it supports the general critique aiming at approaching local audiences in a manner that resembles a self-fulfilling, positive prophecy (Pauly & Eckert, 2002): the study indicates that when audiences’ consumption of local news and interest in them is analysed along with interest in other types of news and with respect to contextual variables, local news could hardly be considered as a general core of audiences’ news consumption because the patterns of interest in local news strongly vary across socio-demographically and geographically specific groups of the national population. To put it simply, context matters—both in cross-national and intra-national perspectives. The U.S. or U.K. experience could not be simply extended to the Czech context and national specifics have to be seriously taken into account, as one size never fits all.

Drawing on these conclusions, a wide area of future research opens. Instead of normative speculations and theoretical assumptions, more thorough, systematic, and comparative inquiries into local audiences need to be conducted, both qualitative (enabling to understand meanings and practices linked with local media consumption) and quantitative (delivering more complex and generalizable evidence). On the one hand, attention—accompanied by focus on national specifics in validity of measures affecting comparative research—should be paid to comparison of specifics as well as similarities of particular local audiences. On the other hand, evidence delivered by comparative research shall be intertwined with general reconsideration of the conceptual apparatus underlying the research of local media and local audiences.

Author note

The research was supported by projects entitled New and old media in everyday life: media audiences at the time of transforming media uses (Czech Science Foundation, GP13-15684P) and Transformation of public and political participation in the context of changing media technologies and practices (Grant Agency of the Masaryk University, MUNI/A/0903/2013).

References

Aldridge, M. (2007). Understanding the local media. New York, NY: Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education.

Ali, C. (2017). Media localism: The policies of place. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois press.

Costera Meijer, I. (2012). Valuable journalism: A search for quality from the vantage point of the user. Journalism, 14 (6), 754–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884912455899

Česká televize [Czech Television]. (2018). History. Retrieved from http://www.ceskatelevize.cz/english/history-in-a-nutshell/

Český rozhlas [Czech Radio]. (2018). General information. Retrieved from http://www.rozhlas.cz/english/generalinformation/

Elvestad, E. (2009). Introverted locals or world citizens? A quantitative study of interest in local and foreign news in traditional media and on the internet. Nordicom Review, 30 (2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0154

Eurostat. (2013). Rural development in the EU: Statistical and economic information. Report 2013. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/statistics/rural-development/2013/full-text_en.pdf

Eurostat. (2016). Urban Europe: Statistics on cities, towns and suburbs, 2016 edition. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/7596823/KS-01-16-691-EN-N.pdf/0abf140c-ccc7-4a7f-b236-682effcde10f

Eurostat. (2017). Digital economy and society. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/main-tables

Fenton, N., Metykova, M., Schlosberg, J., & Freedman D. (2010). Meeting the news needs of local communities. London, England: Media Trust.

Fletcher, R., Radcliffe, D., Levy, D. A. L., Nielsen, R. K., & Newman, N. (2015). Reuters Institute digital news report 2015. Supplementary report. Oxford, England: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Supplementary%20Digital%20News%20Report%202015.pdf

Franklin, B. (Ed.). (2006). Local journalism and local media. Making the local news. London, England: Routledge.

Gulyás, Á. (2003). Print media in post-communist East Central Europe. European Journal of Communication, 18 (1), 81–106.

Gustafsson, K. E., Örnebring, H., & Levy, D. A. L. (2009). Press subsidies and local news: The Swedish case. Oxford, England: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Hess, K., & Waller, L. (2017). Local journalism in a digital world. London, England: Palgrave.

Hollander, B. (2010). Local government news drives print readership. Newspaper Research Journal, 31 (4), 6–15.

Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies. (2017). Special issue about local and regional press, 6 (1). Retrieved from https://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals/view-issue,id=3243/

Lauterer, J. (2006). Community journalism. Relentlessly local. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Macek, J., Macková, A., & Kotišová, J. (2015a). Participation or new media use first? Reconsidering the role of new media in civic practices in the Czech Republic. Medijske Studije, 6 (11), 68–83.

Macek, J., Macková, A., Škařupová, K., & Waschková Císařová, L. (2015b). Old and new media in everyday life of Czech audiences. Research report. Brno: Masaryk University.

Mair, J., Fowler, N., & Reeves, I. (Eds.). (2012). What do we mean by local? Grass-roots journalism – its death and rebirth. Suffolk, England: Abramis Academic Publishing.

McCollough, K., Crowell J. K., & Napoli, P. M. (2016). Portrait of the online local news audience. Digital Journalism, 5 (1), 100–18.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A. L., & Nielsen, R. K. (2017). Reuters institute digital news report 2017. Oxford, England: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20web_0.pdf

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Levy, D. A. L., & Nielsen, R. K. (2016). Reuters Institute digital news report 2016. Oxford, England: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital-News-Report-2016.pdf

Newman, N., Levy, D. A. L., & Nielsen, R. K. (2015). Reuters Institute digital news report 2015. Tracking the future of news. Oxford, England: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Retrieved from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Reuters%20Institute%20Digital%20News%20Report%202015_Full%20Report.pdf

Nielsen, R. K. (Ed.). (2015). Local journalism. The decline of newspapers and the rise of digital media. London, England: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, I. B. Tauris.

Nielsen, R. K. (2016). Folk theories of journalism. The many faces of a local newspaper. Journalism Studies, 17 (7), 840–48.

Ofcom. (2009). Local and regional media in the UK. Retrieved from https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/15957/lrmuk.pdf

Pácl, P. (1997). Hromadné sdělovací prostředky v regionu [Mass media in the region]. Ostrava, Czech Republic: FF Ostravské univerzity.

Pauly, J. J., & Eckert, M. (2002). The myth of “the local” in American journalism. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 79 (2), 310–26.

Pew Research Center. (2012). How people get local news and information in different communities. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/09/26/how-people-get-local-news-and-information-in-different-communities/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Local news in a digital age. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2015/03/05/local-news-in-a-digital-age/

Rothenbuhler, E. W., Mullen, L. J., DeLaurell, R., & Ryu, C. R. (1996). Communication, community attachment, and involvement. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 2, 445–66.

Skogerbø, E., & Winsvold, M. (2011). Audiences on the move? Use and assessment of local print and online newspapers. European Journal of Communication, 26 (3), 214–29.

Televize Nova (2018). [Nova Television]. Retrieved from http://www.novagroup.cz/kdo-jsme/profil

Televize Prima. (2018). [Prima Television]. Retrieved from https://www.iprima.cz/o-ftv-prima

Volek, J. (2007). Regionální žurnalisté v posttransformační etapě: vybrané socioprofesní charakteristiky [Regional journalists in the post-transition phase: selected socio-professional characteristics.]. In Waschková Císařová, L. (Ed.), Regionální média v evropském kontextu. [Regional media in the European context] (pp. 35–50). Brno, Czech Republic: Masarykova univerzita.

Wadbring, I., & Bergström, A. (2017). A print crisis or a local crisis? Local news use over three decades. Journalism Studies, 18 (2), 175–90.

Waschková Císařová, L. (2013). Český lokální a regionální tisk mezi lety 1989 a 2009 [Czech local and regional press between 1989 and 2009]. Brno, Czech Republic: Munipress.

Waschková Císařová, L. (2016). Czech local press content: When more is actually less. Communication Today, 7 (1), 104–17.

Waschková Císařová, L., & Metyková, M. (2015). Better the devil you don’t know: Post-revolutionary journalism and media ownership in the Czech Republic. Medijske Studije, 6 (11), 6–17.

Footnotes

Footnotes

1 Cf. Nielsen, who works with a similar concept called the folk theories of journalism, describing it as, “actually existing popular beliefs about what journalism is, what it does, and what it ought to do.” This understanding might increase readers’ engagement with journalism, but Nielsen takes the concept as a tool enabling researchers to ask new questions to understand journalism better (Nielsen, 2016, pp. 1, 3).

2 Within the Czech media system, the term local media denotes media produced and distributed only at the municipal and district level, while the term regional media refers to media produced and distributed at the regional level (see Waschková Císařová, 2016). However, due multiple reorganization of basic units of state administration in the 20th century, the precise definition of the local and the regional as well as shared understanding of these terms among media producers and audiences struggle with a difficulty—in the 1990s the smallest administrative and political unit, a district, was replaced by a much larger region. This complicated the very existence of “non-national” media, which had to choose their area of production and distribution repeatedly (for more see Waschková Císařová, 2013, pp. 19–20).

3 The amount of internet access, broadband access, and internet use by individuals corresponds to the EU average. In terms of internet access, percentage of households who have internet access at home (all forms of internet use included, population 16–74) was 78% in the Czech Republic, and 81% in the whole of the EU in 2014 (the year of our survey data collection) and 83% in the Czech Republic and 87% in the EU in 2017. Percentage of households (with at least one member aged 16–74) with broadband access was 76% in the Czech Republic and 78% in the EU in 2014, and 83% in the Czech Republic and 85% in the EU in 2017. Internet use by individuals (aged 16–74) was 80% in the Czech Republic and 78% in the EU in 2014, 85% in the Czech Republic and 84% in the EU in 2017 (for more see Eurostat, 2017).

4 It is worthwhile to note that the fact that the participants in the cluster of the indifferents do not express interest in any of the four types of news (local, regional, national, or foreign news) does not imply that they are disinterested in all news or even in other media content. Illustratively, only 21.6% of them are pure news non-consumers while 58.1% of them are interested in soft news (on culture, sports, celebrities, etc.), 31.4% in hard news (on economics, science & technologies etc.), 39.2% of them can be considered as regular book readers, 85.9% watch films and 65.8% watch TV at least once a month. In other words, these participants are indifferent only regarding regionalism of news and must be treated as such.

5 The difference between internet infrastructure at the national level and in rural areas is not as substantial as could be expected. The last data are from 2012 and the percentage of standard broadband coverage at the national level was 98% and in rural areas, 88%. Percentage of households having subscribed to a broadband connection was 59% in 2012 in rural areas and 61% at the national level (Eurostat, 2013). The proportion of our survey participants using the internet on daily basis by degree of urbanization: 65.4% cities; 58.8% towns & suburbs; 57.3% rural areas (proportion of users in cities differs from proportion of users in towns & suburbs and in rural areas at the .5 level; proportion of users in towns & suburbs and in rural areas do not differ significantly) (Macek, Macková, Škařupová, & Waschková Císařová, 2015b; cf. Eurostat, 2016).